Sherman and Alberti History

Search This Blog

Saturday, March 2, 2019

Sherman and Alberti History: Cassius Sherman Freezes to death in 1873

Sherman and Alberti History: Cassius Sherman Freezes to death in 1873: Cassius Sherman stepped from his cabin door January 7, 1873 and was greeted with a soft wind that held the promise of an early sprin...

Cassius Sherman Freezes to death in 1873

Cassius Sherman stepped from his cabin door January 7, 1873 and was greeted with a

soft wind that held the promise of an early spring. Drops of water trickled from the shingled

eave of the roof onto the back of his head and neck. He could hear the distinct

metallic pings of a maul as it hit a splitting wedge. The sound carried

through the air from more than a mile away. His Mormon neighbor was already at

his wood pile. The only other sound in this unexpected mild

morning was the scarcely audible cough of his bedridden mother wheezing through

the cracks of the door planks.

It was nearly twenty miles to Maine Minnesota

It was halfway to noon

when Cassius left the cabin. He was dressed sensibly for unpredictable Minnesota

Cassius was familiar with this land and his neighbors. They

were a tight band of obscure believers, uprooted and chased out of

the Midwest for their Book of Mormon beliefs. About

twenty families made up the core of the community. They shared their resources and labor

according to scripture and prophecy. They had followed Brigham Young for a

while and then parted over polygamy and other beliefs. They called themselves "Cutlerites."

All was working according to plan until he was about mid

trip in his long trek to Maine

The wind had picked up and the heavy gray line on the

horizon was growing thicker. He pulled

the flaps of his fur lined cap down around his ears and tied the leather strap

beneath his chin. The Indian trail was not well marked here. He reached in his

pocket for a strip of pemmican he had purchased at the General Store in

Clitherall. He chuckled to himself, thinking he should have brought along “Walking

Much,” the old Ojibwe outcast who had been sitting silently on a pickle barrel

in the store when he left. That old Indian knew this territory from childhood,

but his walking days are long over.

It was definitely getting colder. There were no good

landmarks out here in the prairie. The

temperature had fallen far below the 32 degrees this morning when he stood

outside his cabin door. The air from his mouth instantaneously formed a cloud

of frosty fog. He could tell Bender had lost the path by his slowed pace, ears

and head down, confused by the blowing snow erasing the trail. The entire canopy of sky above them was now

sullen and ominous, laden heavily with peril for those caught out in its grip.

When it came, it was hard and fast. If he were nearer the

trees lining the Otter Tail

Lake

A half starved dog fell in behind them, his bony rib cage

showing his dire predicament. He followed

for a ways. A small tan and white visage barely visible amidst the swirling

snow as it trotted hopefully behind. Cassius

tossed him a slice of pemmican. The dog wolfed it down and seemed to consider

the consequences and advantages of joining them on their journey in such

weather. He chose wisely, and with tail lowered to half mast, reluctantly headed

back to some unseen Indian camp for shelter. Cassius could have used the

company.

Temperatures had dropped so far that his cheeks and nose

burned as if he had stood too close to a bonfire. He pulled the gloves off his

hands and tried to retie the leather thongs of his fur lined cap. He found his numbed

fingers were not up to that simple task. He clumsily reinserted his hands into

his gloves and pulled them tight with his teeth. He recalled a similar storm in 1867 when he

and the Whiting brothers were caught out by Battle

Lake

The seldom used and poorly marked Indian trail they were on

was now completely obliterated by snow. Bender was

a seasoned horse and abruptly stopped.

Short of actual language his question to Cassius was “what are we doing

out here?” Cassius had to compel him

with the heels of his boots to get him to move.

Shrouded by thick hard driving snow there were no landmarks. Cassius could not see past Bender’s neck and mane. Bender was looking into nothing but a snowy

abyss.

Despite Bender’s reservations and horse sense, Cassius was

confident. At 27 he was in peak physical

condition, a war veteran, a hunter, a trapper and he had weathered similar

storms. He was not aware that this storm

was a killer that would surpass any in recent history. It would rage on for

three days and bury cabins in twenty foot drifts. Hundreds would freeze to

death. Some, like him, would be caught out in the open far from home, and some

would die only a few feet from their cabin or barn door. No one kept accurate

track of the loss of livestock and horses, but the numbers were high.

There is no way to know what thoughts were running through

Cassius’s mind when Bender began to founder in the deepening snow. Did Cassius question his decision to make this

long journey on a day that started out with such promise? It probably centered

on his failing mother left alone in the cabin, possibly too ill to tend the

fire, although he had carried ample wood inside before he left. At some point he probably prayed. Then, after he had lost feeling in his arms

and legs, he probably thought of William Mason, whose boot was spotted by trappers’

months after he froze to death in the 1867 blizzard. Who would find his own boot

sticking up from the snow pack? Probably

that half starved dog, or one of the Indians from the camp he had passed.

Somehow they survived these killing storms in skin covered tee pees and lean-to’s.

After the biting pain and loss of feeling in arms and legs,

some say you fall into a numbing sleep, which is preferable to more painful

avenues to death. There are a lot of untold stories beneath the ground here in Mt.

Pleasant Sherman Mount Pleasant

There is little factual information on how Cassius froze to

death. We know he was on his way to Maine Minnesota

Alpheus Cutler, my charismatic great great grandfather, is not buried here but it was

his prophetic vision that led a small group of pioneering followers into this

remote part of Minnesota

My great grandfather Cutler Almon Sherman is buried here. He was loading wood from his wagon into a boxcar in New Clitherall when the west-bound freight train came in. It scared his team of horses. They jumped, knocking him from the wagon and crushing him between the load of wood and the boxcar.

A Frederick Sherman is buried here. Nina Gould, sister to my

grandmother Lenna Maude Gould, said he was a fur trapper. He was found frozen to death in his shanty

with a match in his hand. It appeared

that, while visiting his traps, he fell into a shallow swamp. His clothes immediately froze to his body and

he died before he could light a fire.

Many family members and followers of Alpheus Cutler are

buried here. They died of pneumonia,

typhoid, tuberculosis, whooping cough, cancer, drowning, accidental gunshot

wounds, suicide, and Minnesota Alexandria

Cassius Sherman froze to death and was found in a similar

way. Cassius was the son of Jacob Sherman, the son of Edward Sherman, who came to America Liverpool , England.

The Mount

Pleasant

Saturday, February 16, 2019

The Last Chapter of "Earl Stories."

“Well, Lrae, while Unkel Dan is staring at the ceiling, why

don’t you show me around the neighborhood.”

“Where are we Lrae?”

“Well, hek, Earl, it ain’t exactly where I amed to bring ya,

but its close enuf. I wanted to show you

these genetikally inhanced broilin hens, cuz theys a pekular new-fangled kind

of berd!”

“When you say broilin hens, you don’t mean that’s the name

of the breed?”

“No, no Earl, these is bein bred speshal for the frying pan,

or the rotissorary. These hens have been dummed down and transfixed by mixin

ther molecular partisipals with them shmoos, and other cartune characters.”

Lrae

pulled out his small flask of lethal corn liquor, and Earl and Lrae continued to

get schnockered as they sat lackadaisically against the damaged remains of the time

machine. Earl is telling Lrae a long

fractured story about the

famous rooster Chanticleer and the crafty fox Reynard when they noticed

something was up.

“Say, Earl, somethins up! Are you seein what I’m seein, or mebbe my

vishun is blurred?”

“These chikens look like they’re on steroids Lrae. Look at the size of those thighs!”

“They luk bigger by the minut!”

“Buggers, they aren’t bigger. They’re closing in on us

Lrae!”

“They got em a meen luk Earl. I thenk these here chikins are sum a them “Angry

Chikins” that’s been stirrin up truble here in the county.”

Earl

and Lrae were suddenly surrounded by a hundred and twenty “Angry Chickens,”

which was exactly twelve per cent of the thousand chickens that were crowded

into this broiler house. Some of the

“Angry Chickens” had beak rings and razor blade spurs, and a nasty ammonia

laced aroma. The ring leader was a

super sized leghorn, who was currently appraising the reason for all the

commotion Earl and Lrae had caused.

“I say, I say, and I repeat unkindly one more time, what

have we here? Appears to me boys,

appears to me boys, that we have here not one, but two inebriated plucked and

puny chickens. I say, plucked and puny

chickens. Do I need to repeat repeat? Plucked and puny! Puny! I say, I said, and said again!”

This

cartoon like rendition of Foghorn, the famous comic strip Leghorn

“I

say, and I say again, what do you scrawny motherless mutants have to say for

yourselves?”

Earl

and Lrae had enjoyed the singing, and were going to ask for an encore, but the

Leghorns were giving them threatening looks. Earl and Lrae looked pale and

sickly leaning against the broken time machine. Their goose bumps were accentuated

beneath the fluorescent fixtures by their nakedness and escalating alarm. Earl

still wore his tin foil hat, even when showering, but he had forgotten why.

“You

boys, you boys, you’ve disrupted our chicken house! We’re “Angry Chickens,” we’re bona fide “Angry

Chickens,” and we, we don’t like being disrupted. We’ll teach you interlopers not to drop in

uninvited! Teach you a lesson you two won’t forget!”

“The “Angry Chickens” pressed

in close, and Earl and Lrae were just about to lose control of their

non-existent bladders, and it appeared a small tear was coming out of Earl’s

non-existent tear duct when the nursery room fairy appeared just in the nick of

time. Earl and Lrae looked at one

another in disbelief at the little fairy dressed in her slightly soiled pearl

and dewdrop dress. The hundred and

twenty “Angry Chickens were also momentarily taken back at the diminutive

winged creature.

In a soft fairy voice you’d expect from a palm sized fairy,

she spoke to Earl, “I am the fairy that normally takes care of well loved

nursery room toys, and when they become too old and decrepit I make them real.”

“What does that have to do with me?”

“I’ve come to make you real Earl!”

Earl

thought about this. Here he was

surrounded by a hundred or more “Angry Chickens” who were bent on mischief, and

out of the blue a little fairy appears with a way out of his dilemma. Just in the nick of time!

The “Angry Chickens” began kicking chicken litter onto the little diaphanous wings of the nursery room fairy to the tune of “Bet my Money on a Bob-Tailed Nag.” Not having ever seen a nursery room fairy they were a bit cautious, particularly since she was taking a swing at them every once in a while with her little wand.

Earl was thinking fast. Was the time machine still operable? How good was Lrae in a real hen house brawl? Why hadn’t these hens been de-beaked? What if the “Leghorns” murdered the little nursery room fairy before she could turn him into a real chicken?

The “Angry Chickens” began kicking chicken litter onto the little diaphanous wings of the nursery room fairy to the tune of “Bet my Money on a Bob-Tailed Nag.” Not having ever seen a nursery room fairy they were a bit cautious, particularly since she was taking a swing at them every once in a while with her little wand.

Earl was thinking fast. Was the time machine still operable? How good was Lrae in a real hen house brawl? Why hadn’t these hens been de-beaked? What if the “Leghorns” murdered the little nursery room fairy before she could turn him into a real chicken?

Lrae interrupted by asking the litter soiled fairy whether Earl would be fighting the “Angry Chickens” as a featherweight or a bantamweight after she made Earl real.

Earl

suddenly realized that this sweet fairy with a developing attitude was about to

do the same number on him as she did on the Velveteen Rabbit. He would be a real chicken in a real chicken

house of “Angry Leghorns!” That couldn’t

be good! Earl kicked a little chicken

litter on the fairy himself in answer to her quest to make him real.

“No thanks, little fairy!

I have an ideal life as a rubber chicken, and at Julie’s I’m at the top

of the pecking order, not the bottom.

There’s also the fact that these chickens here are nearly full grown,

and about to hauled off, electrocuted and butchered.”

All

hundred and twenty “Angry Chickens” stopped kicking chicken litter in unison at

the news.

Again

in unison, they all cocked their heads, and gave their razor spurred ringleader

a questioning cock- eyed look.

“I

say fellows, I say, don’t get your hackles up.

He’s just funning us, just a funning.

Right sport? Ain’t that right?

There’s

never a good time or place to end a story that has no story line so it might as

well be right here. All I can say is if

you read this whole thing bow to stern you are living a sad life, so grab a

life preserver, jump overboard, and swim for shore.

Saturday, January 19, 2019

The Albertis of Eureka Springs: A tale of Insanity and Inheritance - Part 2

If you are a regular reader, and invested in the timeline and history of Albert and Laura, I highly recommend reading Part 1 of this story before you keep going:

Alice is at it again kids. This story, all the research hours and work that have gone in to it have been a beast. I’ve struggled to sit down and write this. I am worried I won’t do it justice and it will consume me whole. It is my Jabberwocky, my Bandersnatch. A pile of documents and facts that I have been staring at for months unclear how to proceed. In Alice Through the Looking Glass, the Jabberwocky is a nonsense poem about a monster that Alice finds in a strange book. It is written in a language that appears to make no sense at all. Eventually she figures out that she is traveling through an inverted land and holds a mirror up to the page and reads the following poem:

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought–

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And, as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One two! One two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

“And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”

He chortled in his joy.

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

Even though Alice can read the words clearly they still don’t make very much sense. My hope for this blog post is that it doesn’t leave you feeling like Alice. Confused, bewildered and ready to just go home.

We're All Mad Here

I obtained medical records for Laura back in September from the Missouri Department of Mental Health. Getting them was a bureaucratic maze of a process. No one could legally confirm the existence of the documents without a court order. There is a process in place to request records from the state without a court order, but only if you know they exist in their archive. That makes sense. Deciding the easier path was to try to obtain a court order, I wrote a letter to the Court Clerk of Vernon County (the county the Nevada State Asylum #3 was located) asking for permission to request Laura’s medical records without knowing if they even existed. It was a long shot but the worst they could say was no, right? A few weeks later I received an envelope from the MO Secretary of State containing a signed copy of the court order issued by a Vernon county judge ordering her medical records, minus treatment notes, to be sent to me. A few weeks after that I got a phone call from the MO Dept of Mental Health confirming my email address and just like that, digital copies of the documents were in my inbox. I had no idea what to expect. I only knew from Laura’s probate records that she was declared insane. Not a single clue as to how or why.

Her medical records show that on December 5th she was admitted to the Robinson Sanitarium by her family doctor, Dr.Ketron, to get some rest. While she was resting, her nephew made quick work of having her declared insane by the Jackson County court on December 16th. She spent Christmas in the Sanitarium and three days later was packed in the back of a State Troopers vehicle and driven 94 miles south to her new home at the Nevada State Hospital #3.

The main piece of evidence in proving Laura’s insanity is a letter written by Guy Bowen. I’ve looked a bit deeper at Guy’s history to try to understand why he was so motivated to have Laura committed and become the ward of her $400,000 estate. At the time he was working as a Freight Agent for the railroad in Kansas City. It is either due to luck, poor health or some creative maneuvering that he evaded serving in both WWI and WWII. He met and married Laura’s niece Zora less than a year after the death of his first wife in 1919. He had a five year old daughter from his previous marriage. It’s hard to believe that he spent much time with Laura Alberti from 1920-1943. The Albertis lived on the East Coast for ten of those years, operating among the social elite of the DC area. Then moved to Eureka Springs for the remainder of the those years, traveling south for winter months to take the mineral waters near Tampa, Florida. I imagine they were very occupied with Albert’s failing health and not making too many trips to Kansas City. Guy and Zora Bowen don’t appear on the scene until after Albert’s death when Aunt Laura became the sole heir of a very healthy estate.

Guy Bowen’s letter states that Laura had no health trouble prior to 1936 when an inward goiter (an enlargement of the thyroid gland) developed and started to cause her “much nervousness”. She was hesitant to have an operation as a doctor told her that removing too little or too much of the thyroid could affect her health and mind. Guy also states in the letter that Albert researched the risks of the surgery and was also concerned that the operation might affect her mind. The next part of the letter explains that Laura had her thyroid removed in 1936 and experienced no mental issues. It wasn’t until the death of her husband in 1940 that her “condition” developed.

The letter says this:

“Each winter she would appear to have no interest in life, be very quiet, until late spring, when she would become very talkative, and nervous, which generally would last until fall. She never caused any trouble to the family or outsiders, and it was only this fall - about November 15th - that her mental condition caused us and outsiders considerable concern. She became unmanageable. Her fears are that people are watching her and following her and that the FBI is protecting her. Her husband did some work in Washington in World War I. She now talks of finishing that cause and is eager to work for the government.”

So what do you think? Sounds a little crazy doesn’t it?

New Year in the Mad House

On the first day of the new year 1944, Laura Alberti turned 63 in a room with bars on the window. The day before she was given the early birthday gift of hydrotherapy treatment to try to adjust her “aggravated” and “aggressive” state.

Her patient history states, “Patient cannot explain any reason for being here except to state that she is now working for Uncle US. She refuses to tell us the date of her birth and when we asked her to confirm her Social History she readily did so, stating it was correct, and telling us to talk more quietly as she did not want the other people around here to know how old she was. We feel confident that she knows all about her birth and birthdate.”

Laura was described by her doctors as extremely noisy and talkative, but also restless, agitated, and hyperactive. She was very friendly and happy at times and at other times surly and belligerent. It tooks three people to hold her down for a physical examination. Her records state that she would talk openly about anything but herself. When asked a personal question, “she immediately makes a sign by crooking her thumb and index finger together, snapping it, and making a lisp with her mouth, and tells us frankly that she isn’t going to answer that question.”

She did share however that her married life was very happy. She told doctors that she worked for eight years as a stenographer for Metropolitan Life. Her husband retired three years after their marriage and they took a trip to Europe spending three years in Italy and France. They traveled all over the US and have lived simply near Eureka Springs, Arkansas since 1929. When asked if she drank alcohol, she responded that she did not but that she “did like a highball”.

Her records paint a pretty clear picture of her feisty personality. I have researched the Alberti’s lives extensively and based on my findings I don’t believe that she was as many crayons short of a box as her family thought she was. Instead I think she was a grieving widow, probably suffering from some seasonal depression and anxiety. Just a little over two years had passed since she buried her husband of 26 years. She likely suffered from a thyroid imbalance. It was also the height of WWII, a stressful and scary time for any person who had already lived through a world war, sane or not. What she tells the asylum doctor about working for the government appears to be plausible, if not entirely true, but everyone thinks what she is saying is a delusion.

First let’s establish some of the timeline and major events in the Alberti’s lives leading up to 1943. These events were found in a mix of newspaper articles, passport applications, census records and of course good old history books.

1913 married in Niagara Falls, NY

1916 Albert has official retirement ceremony from Metropolitan Life in Wilmington, Delaware

Feb 1917 Albert and Laura travel to Tampa, Florida to take the waters

April 1917 United States officially enters WWI and Albert’s son Ralph joins the Navy

1918 WWI ends on November 11

1920 census, Laura and Albert live in the Forest Glen area of Silver Spring, Maryland

1924 Albert and Laura apply for passports to travel to Italy and France

1925 they are living in Italy. Ralph is killed in a hit and run accident in DC and Laura’s mother passed.

1928 they return from Italy through San Francisco

1930 census, Laura and Albert live at 41 Vaughn in Eureka Springs, Arkansas

1932 a large stone fireplace was added to 41 Vaughn house

1933 Albert’s 78th Surprise Birthday Party is held at 41 Vaughn house

1936 Laura has her Thyroid removed

1939 Hitler invaded Poland - WWII begins in Europe

June 1940 Italy enters the war on side of Axis powers

1940 Albert dies on September 18, a nation wide draft is implemented by Executive order that same week

1941 US officially entered WWII

These facts are critical in establishing a baseline for you as a reader and painting a picture of the life Laura and Albert lived. It was an active life full of traveling and entertaining friends. It was also a life of loss and coping with chronic health problems. It was a life that saw two world wars. Just think about what that must have been like for Albert and Laura. It turns out, World War I played a larger part in their lives then I could have ever imagined.

A note in Laura’s medical records stuck with me after I read it, “It is impossible to get the patient to directly admit to any of her ideas, but in various conversations with her she has intimated that she is working with the FBI for her Uncle Sam and that she is engaged in some work connected with the war. She tells that she is unable to give out any information about herself because if she does Uncle Sam would soon get her.”

At face value that certainly sounds like something a crazy person would say. In Laura’s case, most of that statement could have been entirely accurate.

The Albertis and the War Effort

In 1917 the Albertis lived in Forest Glen, Maryland. Just a 25 minute drive from Washington D.C.. Albert’s son Ralph was working as a Cashier at the Merchants Trust Company in D.C. He later joined the Navy and was stationed on the USS Henderson transporting troops to the front line in France. According to an internal MetLife publication called The Intelligencer, Albert may have officially retired but he never really stopped working for the company. He is mentioned over and over in the publication. Recognized for acting as a mentor and aid to offices all over the east coast. In 1917 the company was charged by the US government with selling War Saving Stamps, agents and Veteran Superintendents from all over the country were involved in the effort. Any guesses as to who was recognized for their hard work aiding the war effort? That’s right - Albert Alberti. The men weren’t the only ones involved. The women of MetLife were also contributing. In 1917 the FBI hired a number of stenographers for confidential reporting jobs throughout the war. Now how are you feeling about what Laura told her doctors?

Here’s the catch. I don’t have any proof that Laura was one of those stenographers that worked for the FBI, but I do feel like it’s entirely plausible that she did exactly what she told her doctors she was doing during the war. It’s sad that they treated what she was saying as delusional. Even after Albert’s retirement in 1916, he and Laura were still very involved at the highest levels of the company and especially during wartime. Perhaps even involved in confidential work for the government. I’ll make another assumption here. I would bet my lunch money that they weren’t writing home about it. So it only makes sense that when she started mentioning it to her family upon the outbreak of WWII, well... they thought she was nuts.

The last chapter of this story, part 3, will wrap up what happens to Laura and her estate from 1944 until her death in 1965. How it took me to Eureka Springs to conduct some on the ground investigating that proved very fruitful! I know it's hard to believe but the Alberti Saga gets even more interesting. Stay tuned family!

Thursday, December 27, 2018

Earl's Italian "Alberti Trip" Fund Drive

|

| Earl has a cockamamie idea |

Goal – Raise one million, six hundred ninety six

thousand, seven hundred and eighty nine Italian Lire, and some odd Tuscan florins

in change. At the current exchange rate that comes to a cool grand in American

dollars. Please do not contribute actual Lira since Italy

Purpose – Help fund Megan’s obsession to discover

the beautiful "Alberti Estate” using only the few bread crumb clues that Albert

Anatole Alberti left in his wake. Megan is currently taking Italian lessons and

has booked a flight to Italy

What Do You Get? – If Megan actually finds some living

Italian relatives you can invite yourself to pitch a tent on their lawn, sleep

on their couch, or in some other creative way be an obtrusive American guest

and minimize the cost of your Italian vacation?

What Do I Get ?– As a family member adopted by Megan’s

aunt Julie I will ask if I can go to Italy Guatemala Germany Hawaii

How This Works – I’m not sure! I’m a rubber chicken

with no cerebral cortex, but I have a half-baked cockamamie idea.

Here’s my big idea! I’m asking Alberti fans inside and outside

the tribe to look in the bottom drawer of their bureaus, the dark corners of

their garage, or the storage unit they forgot to pay the rent on. You may find an unworn “Make America Great”

hat, or an unused Rolex watch. I personally will donate a free pass to the Archie

McPhee Rubber Chicken

Museum Seattle

|

| Mini-me |

When enough weird or wonderful artifacts are collected (online or off) they can be used as gifts to the contributors that pledge. For instance a "cheep" level donation might earn you a slightly used hernia support belt, etc. At the “Rooster Cogburn” high end level of say one hundred dollars or more, maybe a mug imprinted with the anatomy of a chicken or a photo of me.

Once the weird stuff has been pledged and collected

maybe one of the

crazier members of the Alberti tribe could host a “Bon Voyage” party at their

home to auction the items off.Monday, December 24, 2018

Grandpa and Grandma Sherman attend the "The Priests of Pallas" Parade."

|

| Float in "Priests of Pallas Parade" in Kansas City, Missouri |

Megan’s great Christmas blog, which included Grandma Maude’s

story of the uninvited Christmas guest, prompted me to see if I had any more

stories about my grandparents, particularly Maude.

I found one story about Maude I had never read that includes the Mardi Gras styled Parade mentioned in the title. But before that there's a little more of Maude's history to share.

The first firm memories of my grandparents (Maude and

Plinnie Sherman) were when I was five years old. Grandma Sherman was 73 years old then, and

even though I was only five years old, I sensed the sadness in her countenance

and the unseen weight she carried on her slumped shoulders. Grandpa was 77, and

was still deemed handsome as an older man. Almost everybody inside and outside the family

addressed him by his initials P.A. Other

than a hearing aid he still carried himself sturdily erect, and I would watch

him hard at work refinishing a table or upholstering a chair in his workshop

behind their house.

Income from the shop was still needed but at this point

church had become the focus of their lives, grandpa more so than grandma. Grandpa

was the patriarch of the family and the pastor of the nearby Gudgell

Park Sharon

Maude, like many women of that era, deserves some special

distinction for the childbearing, childrearing, and the heartbreak and unbearable

suffering from losing children before their time.

After Maude was joined by four other sisters

the family outgrew the small cabin and their father Winfield Gould built a bigger

framed house on their homestead that adjoined his father George Gould’s

homestead.

I imagine it being very scenic and all the

children grew up close to the lake where they played, swam, skated, and walked

around its shores to school.

Grandpa George Gould was always interested in

the children’s lessons and liked to have them read to him. He would pace the floor with his hands

crossed behind his back as they read.

Now and then he would stop his pacing and reach up to take down a piece

of dried smoked beef or ham from its nail on the ceiling and shave off thing pieces

for the grandchildren to eat.

When Grandpa George Gould died of a kidney

ailment Maude was sixteen and she went to live with her grandma, Ella Whiting,

Grandpa George’s widow. Nina says Maude had a nice bedroom of her own with

double windows, a big closet and a rag carpet on the floor. There was a wash stand with a big white wash

bowl and pitcher on it. Nina sounded a little envious.

It was at this point that Plinnie Sherman, my

grandfather, came a courting. Nina says

he was a third cousin, and I will defer to that, always thinking they were

closer cousins than that. I’m not good

with figuring out relationships, so third cousins it is until proven otherwise.

Nina

says he came courting from the town of Maine Minnesota Independence , Missouri

Maude traveled to Independence River

Boulevard Independence

I’m going to skip over the many early moves and family tragedies of my grandparents and get to a surprising window into their early lives that I so wrongly assumed was borderline boring.

Nine years younger than Maude, Nina came to

town for an extended visit with her in 1908.

Plinnie and Maude took her to the theater, and several parks where she says

she rode every ride. I wish Nina would

have named the Parks, as there were eight parks in and around Kansas City Fairyland Park Fairmount Park Mount Washington Park Stone Church

Nina was betrothed to Orison Tucker, and he

was begging her to come back home to Minnesota

Plinnie intervened and told Nina that if she

would just stay until October 5th, he and Maude would take her to

see the Priest of Palace Parade in Kansas

City Minnesota

Nina said she did stay. Maud and Plinnie took her on the trolley to Kansas City

I had to look it up since I had never heard

of it!

Her beau, Orison, was quite religious and

might not have approved of a festival honoring Pallas Athene, ancient goddess

in Greek mythology. The correct spelling was “Priests of Pallas Parade,” and

the floats in the parade would surpass anything you’ve seen in the Rose Bowl

Parade! Check out additional images on the internet. Crazy!

I just wanted to add this little tribute to

Maude, my grandmother, who looked so sad when she was older. She was one of

those stalwart courageous women who are so often overlooked in history.

Sunday, December 23, 2018

Christmas Past: Memories of an Unusual House Guest

I recently spent a few hours listening to my grandmother and her siblings recount stories of their childhoods. Seated around a coffee table, they thumbed through small piles of artifacts from their lives. While I listened and watched, I snapped photos of the old family photographs and crumbling newspaper clippings...attempting to preserve the past.

Eventually their voices and laughter became comforting white noise as my mind drifted off and started to imagine their words playing in front of me like an old movie.The scenes floating around and sometimes falling into place on the family history timeline that constantly extends in my brain.

Aunt Ruth presented a small tote that afternoon containing even more treasures. More long forgotten photos, scrapbooks and stories to investigate. I spent some time with these new family treasures this week and compared each item to what “The Box” contains. What immediately stood out was the growing collection of Christmas tales. A few I have heard before, and one new one that caught my attention about a curious visitor that appeared during an 1890’s Minnesota Christmas Eve in a little log cabin on the banks of a place called Silver Lake.

"By the mid-19th century, the first wave of white settlers arrived on the north shore of an unnamed lake, situated on the fertile plains of the Minnesota territory. Primarily English-speaking immigrants from England, Ireland, and Scotland, many of these settlers were descendants of families who had already lived for generations in America; transplants from the East coast who came to lay claim to the land and to seek their fortunes on the edge of the ‘Big Woods’ of Minnesota. These ‘wheeler-dealers’, who bought low and sold high, would eventually name the settlement and its body of water, “Silver Lake”.

Then the lure of cheap farmland later brought Czech and Polish immigrants; hardworking people who established their own churches, cemeteries, schools, cultural halls, saloons, farms, and the vibrant downtown business community of Silver Lake.

If you have ever read Little House on the Prairie books, the descriptions of this Christmas setting in a cabin in the wilderness will sound very familiar. I think Laura Ingalls Wilder could have been their neighbor. She actually wrote a book called, By the Shores of Silver Lake, which I don’t remember reading as a kid. I was a huge Little House on the Prairie fan. The Silver Lake in her story is in South Dakota, but the accounts of life for an early Midwestern settler were likely similar state to state.

Now that we've covered some of the historical facts, let’s make like the ghost of Christmas past and take a trip back 128 years to Otter Tail County, Minnesota, to the one room cabin of Leonard Sherman’s grandparents, Winfield and Ella Gould.

It was Christmas Eve and a blizzard was raging outside, but inside, their little family was busy preparing for Christmas. The children, Leon, Winfield Jr, Maude (Leonard’s mother) and Hallie made popcorn balls, taffy and toasted hazelnuts with their Mother. They hung their fur stockings by the fire, sang hymns and listed to their “Pa” read the Christmas story from the bible.

"The boys, Leon and Winnie, could pull the taffy into long ropes to wind round and round inside a plate, which they set on a pan of snow to harden quickly, so it could be cut up into small, buttery morsels to eat."

After the baking was done, the children were all sent to bed. Like most kids on Christmas Eve they couldn’t sleep due to the anticipation of morning. Their parents stuffed each stocking, blew out the candle and turned in for the night. The two girls, Maude and her younger sister Hallie, stayed wide awake staring at their packed stockings and wondering what was inside.

“They then heard the door softy unlatch. It swung open and a tall Indian walked in wrapped in his blanket. He looked around the room, moved softly on moccasined feet to the fire where he warmed a dried his snowy blanket, then wrapping it about him lay down on the floor to sleep.”

Imagine being a young child and laying terrified in your bed while a stranger decided to take a nap in your living room. The story goes on to describe the chilling howl of wolves outside and the wet splash of snow on the window. Whoever wrote this was a very dramatic storyteller. Maybe that runs in the family? Eventually the whole house fell asleep and awoke the next morning to meet their interesting overnight guest. He was invited to stay and eat Christmas breakfast with them, but remained sitting on the floor, wrapped in his blanket, with his back to the log wall.

The children went about opening their stockings but keeping their distance from the Indian man. The girls found their familiar old rag dolls with newly embroidered faces and clothes. Each child received cloth moccasins, knitted red mittens, popcorn balls and maple sugar doughnuts. The boys found caps and a homemade checker board with black and white buttons for playing pieces. Their mother must have been a very crafty woman, because she also made a Jack in the Box from an old coiled bed spring, fastened inside of a box, with a dried apple head and black yarn hair. I have always hated these things. A terrifying spring loaded contraption that pops out at you when you least expect it. It’s more torture device than toy if you ask me. I imagine this homemade version looked something akin to a shrunken voodoo head.

After the boys had a few turns opening the lid of the box and probably tormenting their little sisters, their mother directed them to share it with the Indian man.

“The Indian took the box and moved the hook that fastened the cover down. Up popped the dried apple head and BANG went the Indian’s head back against the logs. He rubbed the back of his head and shook with silent laughter. Encouraged by his laughter, all the children edged in a little closer. The Indian took the closed box and fastened it, then cautiously unhooked it again. Up popped the apple head and BANG went his head against the logs again. This time he laughed until tears ran down his cheeks and the youngsters all laughed with him.”

The children lost their fear of the strange guest and they all gathered around the table and eat buckwheat cakes and bacon, “swimming” with maple syrup. The story ends, “that was a Christmas they always remembered.” I bet these events were the hot conversation topic in Silver Lake for weeks after.

This story is told from the perspective of another Gould sibling that wasn’t born when these events occurred and it isn’t signed or dated. I’m left to assume it took place in the 1890s based on the history of Silver Lake and the descriptions of the Gould children. I am so curious about where the Indian man came from. Did he have a habit of sleeping in other peoples cabins?

In 1862, before the area was called Silver Lake, the Sioux Indians were fighting back against the new settlers. They destroyed most of the early settlement, crops and livestock. Relations were not good, but the government was eager to see these wild places tamed and encouraged locals to organize, scout, track and kill the Sioux. By 1874 the climate was more stable and permanent homes were built near the shores of the lake. Perhaps the Gould's Christmas guest was an old Sioux man. A remnant of a tribe long disappeared from the area. A straggler that decided to assimilate instead of leave. However it happened, it feels like a speck of good Karma that our ancestors showed him kindness and love on Christmas day.

Eventually their voices and laughter became comforting white noise as my mind drifted off and started to imagine their words playing in front of me like an old movie.The scenes floating around and sometimes falling into place on the family history timeline that constantly extends in my brain.

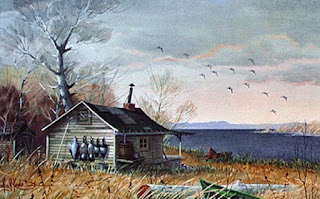

|

| A cabin on Silver Lake |

"By the mid-19th century, the first wave of white settlers arrived on the north shore of an unnamed lake, situated on the fertile plains of the Minnesota territory. Primarily English-speaking immigrants from England, Ireland, and Scotland, many of these settlers were descendants of families who had already lived for generations in America; transplants from the East coast who came to lay claim to the land and to seek their fortunes on the edge of the ‘Big Woods’ of Minnesota. These ‘wheeler-dealers’, who bought low and sold high, would eventually name the settlement and its body of water, “Silver Lake”.

Then the lure of cheap farmland later brought Czech and Polish immigrants; hardworking people who established their own churches, cemeteries, schools, cultural halls, saloons, farms, and the vibrant downtown business community of Silver Lake.

|

| Silver Lake 1880 |

If you have ever read Little House on the Prairie books, the descriptions of this Christmas setting in a cabin in the wilderness will sound very familiar. I think Laura Ingalls Wilder could have been their neighbor. She actually wrote a book called, By the Shores of Silver Lake, which I don’t remember reading as a kid. I was a huge Little House on the Prairie fan. The Silver Lake in her story is in South Dakota, but the accounts of life for an early Midwestern settler were likely similar state to state.

Now that we've covered some of the historical facts, let’s make like the ghost of Christmas past and take a trip back 128 years to Otter Tail County, Minnesota, to the one room cabin of Leonard Sherman’s grandparents, Winfield and Ella Gould.

|

| Winfield and Ella Gould at Silver Lake |

It was Christmas Eve and a blizzard was raging outside, but inside, their little family was busy preparing for Christmas. The children, Leon, Winfield Jr, Maude (Leonard’s mother) and Hallie made popcorn balls, taffy and toasted hazelnuts with their Mother. They hung their fur stockings by the fire, sang hymns and listed to their “Pa” read the Christmas story from the bible.

"The boys, Leon and Winnie, could pull the taffy into long ropes to wind round and round inside a plate, which they set on a pan of snow to harden quickly, so it could be cut up into small, buttery morsels to eat."

After the baking was done, the children were all sent to bed. Like most kids on Christmas Eve they couldn’t sleep due to the anticipation of morning. Their parents stuffed each stocking, blew out the candle and turned in for the night. The two girls, Maude and her younger sister Hallie, stayed wide awake staring at their packed stockings and wondering what was inside.

“They then heard the door softy unlatch. It swung open and a tall Indian walked in wrapped in his blanket. He looked around the room, moved softly on moccasined feet to the fire where he warmed a dried his snowy blanket, then wrapping it about him lay down on the floor to sleep.”

Imagine being a young child and laying terrified in your bed while a stranger decided to take a nap in your living room. The story goes on to describe the chilling howl of wolves outside and the wet splash of snow on the window. Whoever wrote this was a very dramatic storyteller. Maybe that runs in the family? Eventually the whole house fell asleep and awoke the next morning to meet their interesting overnight guest. He was invited to stay and eat Christmas breakfast with them, but remained sitting on the floor, wrapped in his blanket, with his back to the log wall.

The children went about opening their stockings but keeping their distance from the Indian man. The girls found their familiar old rag dolls with newly embroidered faces and clothes. Each child received cloth moccasins, knitted red mittens, popcorn balls and maple sugar doughnuts. The boys found caps and a homemade checker board with black and white buttons for playing pieces. Their mother must have been a very crafty woman, because she also made a Jack in the Box from an old coiled bed spring, fastened inside of a box, with a dried apple head and black yarn hair. I have always hated these things. A terrifying spring loaded contraption that pops out at you when you least expect it. It’s more torture device than toy if you ask me. I imagine this homemade version looked something akin to a shrunken voodoo head.

After the boys had a few turns opening the lid of the box and probably tormenting their little sisters, their mother directed them to share it with the Indian man.

“The Indian took the box and moved the hook that fastened the cover down. Up popped the dried apple head and BANG went the Indian’s head back against the logs. He rubbed the back of his head and shook with silent laughter. Encouraged by his laughter, all the children edged in a little closer. The Indian took the closed box and fastened it, then cautiously unhooked it again. Up popped the apple head and BANG went his head against the logs again. This time he laughed until tears ran down his cheeks and the youngsters all laughed with him.”

The children lost their fear of the strange guest and they all gathered around the table and eat buckwheat cakes and bacon, “swimming” with maple syrup. The story ends, “that was a Christmas they always remembered.” I bet these events were the hot conversation topic in Silver Lake for weeks after.

This story is told from the perspective of another Gould sibling that wasn’t born when these events occurred and it isn’t signed or dated. I’m left to assume it took place in the 1890s based on the history of Silver Lake and the descriptions of the Gould children. I am so curious about where the Indian man came from. Did he have a habit of sleeping in other peoples cabins?

In 1862, before the area was called Silver Lake, the Sioux Indians were fighting back against the new settlers. They destroyed most of the early settlement, crops and livestock. Relations were not good, but the government was eager to see these wild places tamed and encouraged locals to organize, scout, track and kill the Sioux. By 1874 the climate was more stable and permanent homes were built near the shores of the lake. Perhaps the Gould's Christmas guest was an old Sioux man. A remnant of a tribe long disappeared from the area. A straggler that decided to assimilate instead of leave. However it happened, it feels like a speck of good Karma that our ancestors showed him kindness and love on Christmas day.

I hope to share a few more family Christmas stories over the next week. I find them so charming and a great way to get in the true spirit of the holiday season.

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Sharon Lee Sherman (my sweet sister Sherry)

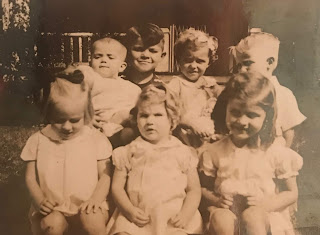

|

| Sister Sherry |

Sharon Lee Sherman was born October 24, 1938, the same week

that Orson Welles caused panic in the U.S. when he broadcast a realistic radio

drama on CBS that made listeners think the world was being invaded by

Martians. Hitler was causing trouble in

Europe, but things were peaceful on Huttig Street where no one was concerned

about world events, and two-year-old Judy and four-year-old Dale were focused

on the brown eyed newborn that mom had brought home. As a child, we called her

Sherry.

|

| Dale holding ornery Sharon |

He would sell Mom sewing needles, buttons, vanilla extract, and always a small can of Watkins’s liniment that she used to treat the psoriasis on the back of her hand.

The sinister-looking Watkins’s Salesman once gave me a ride home

when I was in first grade on his three-wheeled company scooter, probably thinking he could

wheedle Mom into buying more products. I

straddled the box of product that sat behind him, and when he didn’t seem to be

slowing down at our house I assumed he was not only smarmy but a kidnapper, and

I bailed out in front of the Holy Roller Hickman’s house. There was a lot of

gravel there close to the road drain, and a lot of it ended up embedded in my

forearms when I tried to slow down my head-long skid.

The salesman’s tonic might have helped mom’s lethargy

a little with its alcohol content but I think mom’s sickness was probably a

message Sherry was sending her that she didn’t like tight spaces and needed

more room in the cramped womb. Personal space was a cherished thing for my

middle sister Sherry. As it turned out,

there was no need to worry about Sherry’s temperament (disposition) being

permanently affected. According to Mom, Sherry

arrived in this world a “very happy baby!” In her notebook, she adds:

“She woke up with happy sounds and went to

sleep cooing. I called her baby

dumpling.”

Mrs. Hickman, Mom’s

close friend and Holy Roller neighbor, called Sherry applesauce. She said she picked that name because Sherry

was so sweet. There is one little feature in Sherry’s make-up now that

I think about it, that seems incongruous for someone so sweet and friendly that

a neighbor would nickname her “applesauce.” There may have been a trace of tart

Granny Smith Apple in that sauce.

One instance of Sherry’s not-so-sweet behavior is when she was a very young pre-schooler. Sherry evidently

liked having her own personal space and she erected a little imaginary perimeter fence around

her domain and protected it fiercely.

Mom writes this:

Mom writes this:

Judy

was delighted to have a little sister and smothered her with attention. Sherry finally resorted to biting Judy to be

able to be free of her attention awhile. This went on for a while. I tried to talk to Sherry and Judy to set

things right again. One day, while I was on the phone, Judy came to me with

tears in her eyes and showed me a big bruise on her arm where Sherry had bitten

her. I told her I just didn’t know what

to do – that I guessed she would have to bite her back. Then she (Judy) really started crying – “I

can’t, I love her too much!” Sherry was

watching big-eyed, all this time, and to my knowledge, she never bit Judy or

anyone else after that.”

The second example of Sherry’s personal

space requirements comes a few years later when Sherry and Judy were around

five and seven. Sherry had broken both bones in her forearm when Dale tried to

flip her over a clothesline with his feet at Grandpa Sherman’s house. In a letter to Leonard, my mother writes this:

“Judy follows Sherry trying to find something she

can do for her, until Sherry gets provoked and says ‘Quit that following me

around!

Sherry cracked Mom up

repeatedly with odd little sayings she would blurt out. Mom couldn’t remember

them later on, probably because they were so off the wall and preposterous. Later in life Mom writes this about Sherry.

“Sharon Lee

was the most original in the cute things she said, I thought I never would

forget them, but I have!”

Mother had forgotten she had

written this little jewel I found in one of the letters she wrote to Leonard in

1944.

“Sherry was asking Judy if she needed teeth this

morning, said if she did, she’d plant her some seed for some false teeth.”

There was another one I unearthed. A neighbor was rebuilding his house after a fire, and Sherry asked mother if he was re-building his house so he could burn it down again?

There are little glimpses of

Sherry’s childhood world in the letters my parents exchanged in 1944. Sherry would have been five and in

kindergarten. Here are some snippets from Leonard’s letters: “Hello Sherry, my, I

bet you will make a good farmer and housekeeper too, helping mama and taking

care of Danny and cooking.”---- “Dear Sherry, I hope your arm is all well and

strong the next time I see you. Did you

pass in school?”

“Sherry cried, and

wouldn’t go to school today but felt good as soon as the danger of school

was over.”

This opposite attitude about

school is in another letter: “Even Sherry is in school, she cried until I let

her go.” “Sherry and Judy took their lunch today. The magician is coming again, 15 cents each.”

“Sherry still says a lot of funny

things!”

Mom wrote this later in life about

Sherry’s helpful nature, when she was five or six.

|

| Sherry on the left and Ruthie on the right. Another dog I've forgotten in the middle |

“I had a corner cabinet with nice cups and saucers,

each one different. Little Sherry loved

to dust and arrange them. Our floor in

the dining room was not really level and the corner cabinet toppled over.

Many of the cups and saucers were broken or cracked.

Sherry turned so pale that even her lips lost color – I was afraid she was going to faint and held her to me and tried to comfort her. Finally, I told her that she would probably get me lots more when she grew up.”

Many of the cups and saucers were broken or cracked.

Sherry turned so pale that even her lips lost color – I was afraid she was going to faint and held her to me and tried to comfort her. Finally, I told her that she would probably get me lots more when she grew up.”

While I was known for upchucking

explosively if I saw something disgusting, or if I caught a glimpse of someone

else upchucking, Sherry was a legendary fainter. When Dr. Hink cut the cast off her arm, she

fainted straight away. A career in nursing was not on the

table.

Sherry seemed willing

to help with any request her big brother Dale proposed, even after his attempt

to flip her over the clothesline with his feet. Sherry seemed

to be the “go-to” when Dale needed a partner for a circus stunt, or a victim to

test a theory on.

One day Dale gave Sherry detailed instructions

on how she could catch a bumblebee in her hands without getting stung, an

experiment they carried out near the gas meter on the driveway side. Mom had planted some flowers there in

the false hope that they wouldn’t be trampled. I imagine Dale was standing behind her as the bumblebee hovered and buzzed above one of Mom’s purple zinnias. I can hear Dale say “When you cup your hands around

it Sherry, make sure the bumblebee is completely in the dark. If it sees any daylight he’ll sting you.” The

results of the experiment came out as you might expect.

Sherry told me this little anecdote about a crabby neighbor with a short fuse. She told it with such pleasure, that it might make you question her sweet nature. Two doors down toward Blakeley’s corner grocery stood a large house on a large lot, owned by a man seldom seen. He hated children, and they must have been in school the day he bought the house, not suspecting that when the last school bell rang the neighboring yards would overflow with unpredictable and sometimes destructive children. Counting the six or seven homes that were the closest to him I can name fifteen children.

Sherry told me this little anecdote about a crabby neighbor with a short fuse. She told it with such pleasure, that it might make you question her sweet nature. Two doors down toward Blakeley’s corner grocery stood a large house on a large lot, owned by a man seldom seen. He hated children, and they must have been in school the day he bought the house, not suspecting that when the last school bell rang the neighboring yards would overflow with unpredictable and sometimes destructive children. Counting the six or seven homes that were the closest to him I can name fifteen children.

He hunkered down in his big house and even nailed a no-trespassing sign on the tree where you entered his long curving driveway. We

ignored the sign and used the drive frequently. The drive had a nice dip and curves

in it when we rode our bikes down it, and then we’d coast all the way around to the

back to where his garage sat. It was also good for sledding.

He wouldn’t answer the doorbell when kids like me were collecting for the March of Dimes, or selling scout

tickets and Christmas holly, etc. He must have had one of those little eye holes

in the door to screen out small salesmen. His first option was to call the

police when we trespassed.

Sherry said she and some neighbor friends

filled a paper sack with some cow dung, placed it on his front porch, set a

match to the paper sack, rang the doorbell, and then ran and hid behind the bushes.

Squinting with one eye through his little peephole and seeing no one he might

have marked it up as just another harmless prank to irritate him until he saw

a whisper of black smoke rise from his porch.

Alarmed, he unlocked the door, opened it, and saw the burning sack. He

vigorously stomped out the fire wishing no doubt he had bought a house in a

quieter area with no school nearby. We

were in an inner-city neighborhood with a few chickens but no cows, which brings

into question the origin of the shit in the sack. We had a surplus of mixed-breed dogs. I’m sure that whatever animal

contributed to the poop, it was on the crank's shoes or slippers as he tracked back

through the house to the phone, where he immediately called the police.

Sherry, not one to flee the

scene of a crime, says that when the policeman left the crime scene and passed them hiding behind the

shrubbery, he whispered “Good job kids!

Sherry, not one to flee the

scene of a crime, says that when the policeman left the crime scene and passed them hiding behind the

shrubbery, he whispered “Good job kids! Sherry was Dale's go-to when they were young, and it was again Sherry that Dale went to in High School when he needed a note signed that came from the Northeast High School Principal. A tidal wave of correspondence arrived in our mailbox concerning Dale's absenteeism. Dale and his buddy Wally would skip school and spend the day in the pool hall next to the barbershop in Fairmount.

Sherry penned Mother's signature so accurately it would have taken a handwriting expert to detect the difference and in addition improvised novel works of fictional excuses for Dale's absences.

Sherry's big reward for the forgeries came after Mom found the cache of letters during a routine flipping of Dale's mattress. Mom took Dale to the Naval Recruiting Station in Kansas City and he was soon boarding a train at the Union Station headed to boot camp in San Diego California. Sherry says Dale left his car for her to drive to school her senior year. It wasn't the 32 Ford Coupe with the rumble seat or the big Chrysler he bought for less than a hundred dollars. It must have been the 1939 straight-eight Oldsmobile. I've lost track of which one it was, but it had a stick shift.

Sherry couldn’t wait to earn a

little money of her own. She says she was never overly fond of schoolwork. At a young age, she started babysitting for our

next-door neighbor's boys, Kenny and Johnny Musgrave, and then any other

neighbor kid that Judy wasn’t already babysitting. She snagged a job at the

Five and Dime in Fairmount. and worked there for two weeks helping with inventory

and neatly stocking the shelves. She earned praise from the owner until he found she

was only 14 and too young to be legally working. She found a job soon after working at the

Byam Theatre, possibly with a recommendation from Dale, who had been

a dependable worker at the Byam Pharmacy cleaning up and delivering

prescriptions on his bicycle.

In her junior year while still at Northeast High School Sherry found a part-time job at a plastics factory in the Italian District, near the industrial west bottoms. She would board a city bus to school that entailed several transfers, and then after school, she would catch a bus to the job. Following work she would board another bus for the long ride home. I imagine after a four-hour shift it was probably dark by the time she made the last bus transfer to Mount Washington. Then the last bus would leave her at Fairmount and then she would walk down Huttig in the dark to our home.

Sherry says Mom was a terrible driver. She would get mad when Sherry told her she was driving too close to the edge of the road. I remember Mom telling me that her Dad was a terrible driver, and would drive too close to the edge. Mom said if you criticized him, or tried to warn him of an approaching train, or some obstacle in the road, he would just slam on his brakes with no concern about who was behind him.

Sherry was popular and pretty and dated early. She was active in Zion's League at Gudgell Park and she had plans to marry Vernon Sperry. He had a mile-wide jealous streak and was upset when Sherry made plans to attend Graceland College in Lamoni, Iowa. He showed up at the house with his mother and they angrily took back the ring he had given her. They also took the hope chest and all of its contents. Vernon's comment that Sherry was just attending Graceland to meet boys turned out to have some merit. That's where she met her future husband David Ackley.

There are a number of

interesting little bits and pieces of information I have written down about

Sherry that I can’t thread together in any coherent manner.

Sherry’s favorite meal at

Fairmount Elementary was cornbread and beans with vinegar.

Sherry remembers a female high

school science teacher who had the mannerisms of a man. She wore an ill-fitting

wig, and while lecturing she would sit on the edge of her desk constantly

adjusting her girdle and pulling up her bra. When the students learned she was

allergic to roses they would bring them, and she would place them on her desk

instead of throwing them out. Then they

would have a substitute teacher for several days until she recovered.

A few years ago a sudden change in temperature caused Frostflowers to erupt in the old abandoned homestead at the bottom of the hill. It looked like iced cotton candy spinning out from the fissures at the base of Ironweed and other weedy plants. I stood with my sisters Judy and Ruth in the middle of this weed garden of Frostflowers stunned by the beauty of it. It was momentary art that none of us had witnessed in all our combined years. The sun soon melted them but it made me reflect on the fleeting nature of our existence. I realize we are all Frostflowers, impermanent and fragile.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)