|

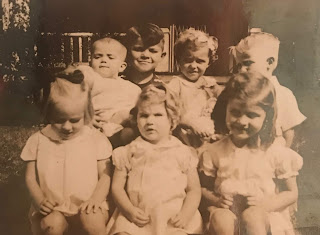

| Sister Sherry |

Sharon Lee Sherman was born October 24, 1938, the same week

that Orson Welles caused panic in the U.S. when he broadcast a realistic radio

drama on CBS that made listeners think the world was being invaded by

Martians. Hitler was causing trouble in

Europe, but things were peaceful on Huttig Street where no one was concerned

about world events, and two-year-old Judy and four-year-old Dale were focused

on the brown eyed newborn that mom had brought home. As a child, we called her

Sherry.

|

| Dale holding ornery Sharon |

He would sell Mom sewing needles, buttons, vanilla extract, and always a small can of Watkins’s liniment that she used to treat the psoriasis on the back of her hand.

The sinister-looking Watkins’s Salesman once gave me a ride home

when I was in first grade on his three-wheeled company scooter, probably thinking he could

wheedle Mom into buying more products. I

straddled the box of product that sat behind him, and when he didn’t seem to be

slowing down at our house I assumed he was not only smarmy but a kidnapper, and

I bailed out in front of the Holy Roller Hickman’s house. There was a lot of

gravel there close to the road drain, and a lot of it ended up embedded in my

forearms when I tried to slow down my head-long skid.

The salesman’s tonic might have helped mom’s lethargy

a little with its alcohol content but I think mom’s sickness was probably a

message Sherry was sending her that she didn’t like tight spaces and needed

more room in the cramped womb. Personal space was a cherished thing for my

middle sister Sherry. As it turned out,

there was no need to worry about Sherry’s temperament (disposition) being

permanently affected. According to Mom, Sherry

arrived in this world a “very happy baby!” In her notebook, she adds:

“She woke up with happy sounds and went to

sleep cooing. I called her baby

dumpling.”

Mrs. Hickman, Mom’s

close friend and Holy Roller neighbor, called Sherry applesauce. She said she picked that name because Sherry

was so sweet. There is one little feature in Sherry’s make-up now that

I think about it, that seems incongruous for someone so sweet and friendly that

a neighbor would nickname her “applesauce.” There may have been a trace of tart

Granny Smith Apple in that sauce.

One instance of Sherry’s not-so-sweet behavior is when she was a very young pre-schooler. Sherry evidently

liked having her own personal space and she erected a little imaginary perimeter fence around

her domain and protected it fiercely.

Mom writes this:

Mom writes this:

Judy

was delighted to have a little sister and smothered her with attention. Sherry finally resorted to biting Judy to be

able to be free of her attention awhile. This went on for a while. I tried to talk to Sherry and Judy to set

things right again. One day, while I was on the phone, Judy came to me with

tears in her eyes and showed me a big bruise on her arm where Sherry had bitten

her. I told her I just didn’t know what

to do – that I guessed she would have to bite her back. Then she (Judy) really started crying – “I

can’t, I love her too much!” Sherry was

watching big-eyed, all this time, and to my knowledge, she never bit Judy or

anyone else after that.”

The second example of Sherry’s personal

space requirements comes a few years later when Sherry and Judy were around

five and seven. Sherry had broken both bones in her forearm when Dale tried to

flip her over a clothesline with his feet at Grandpa Sherman’s house. In a letter to Leonard, my mother writes this:

“Judy follows Sherry trying to find something she

can do for her, until Sherry gets provoked and says ‘Quit that following me

around!

Sherry cracked Mom up

repeatedly with odd little sayings she would blurt out. Mom couldn’t remember

them later on, probably because they were so off the wall and preposterous. Later in life Mom writes this about Sherry.

“Sharon Lee

was the most original in the cute things she said, I thought I never would

forget them, but I have!”

Mother had forgotten she had

written this little jewel I found in one of the letters she wrote to Leonard in

1944.

“Sherry was asking Judy if she needed teeth this

morning, said if she did, she’d plant her some seed for some false teeth.”

There was another one I unearthed. A neighbor was rebuilding his house after a fire, and Sherry asked mother if he was re-building his house so he could burn it down again?

There are little glimpses of

Sherry’s childhood world in the letters my parents exchanged in 1944. Sherry would have been five and in

kindergarten. Here are some snippets from Leonard’s letters: “Hello Sherry, my, I

bet you will make a good farmer and housekeeper too, helping mama and taking

care of Danny and cooking.”---- “Dear Sherry, I hope your arm is all well and

strong the next time I see you. Did you

pass in school?”

“Sherry cried, and

wouldn’t go to school today but felt good as soon as the danger of school

was over.”

This opposite attitude about

school is in another letter: “Even Sherry is in school, she cried until I let

her go.” “Sherry and Judy took their lunch today. The magician is coming again, 15 cents each.”

“Sherry still says a lot of funny

things!”

Mom wrote this later in life about

Sherry’s helpful nature, when she was five or six.

|

| Sherry on the left and Ruthie on the right. Another dog I've forgotten in the middle |

“I had a corner cabinet with nice cups and saucers,

each one different. Little Sherry loved

to dust and arrange them. Our floor in

the dining room was not really level and the corner cabinet toppled over.

Many of the cups and saucers were broken or cracked.

Sherry turned so pale that even her lips lost color – I was afraid she was going to faint and held her to me and tried to comfort her. Finally, I told her that she would probably get me lots more when she grew up.”

Many of the cups and saucers were broken or cracked.

Sherry turned so pale that even her lips lost color – I was afraid she was going to faint and held her to me and tried to comfort her. Finally, I told her that she would probably get me lots more when she grew up.”

While I was known for upchucking

explosively if I saw something disgusting, or if I caught a glimpse of someone

else upchucking, Sherry was a legendary fainter. When Dr. Hink cut the cast off her arm, she

fainted straight away. A career in nursing was not on the

table.

Sherry seemed willing

to help with any request her big brother Dale proposed, even after his attempt

to flip her over the clothesline with his feet. Sherry seemed

to be the “go-to” when Dale needed a partner for a circus stunt, or a victim to

test a theory on.

One day Dale gave Sherry detailed instructions

on how she could catch a bumblebee in her hands without getting stung, an

experiment they carried out near the gas meter on the driveway side. Mom had planted some flowers there in

the false hope that they wouldn’t be trampled. I imagine Dale was standing behind her as the bumblebee hovered and buzzed above one of Mom’s purple zinnias. I can hear Dale say “When you cup your hands around

it Sherry, make sure the bumblebee is completely in the dark. If it sees any daylight he’ll sting you.” The

results of the experiment came out as you might expect.

Sherry told me this little anecdote about a crabby neighbor with a short fuse. She told it with such pleasure, that it might make you question her sweet nature. Two doors down toward Blakeley’s corner grocery stood a large house on a large lot, owned by a man seldom seen. He hated children, and they must have been in school the day he bought the house, not suspecting that when the last school bell rang the neighboring yards would overflow with unpredictable and sometimes destructive children. Counting the six or seven homes that were the closest to him I can name fifteen children.

Sherry told me this little anecdote about a crabby neighbor with a short fuse. She told it with such pleasure, that it might make you question her sweet nature. Two doors down toward Blakeley’s corner grocery stood a large house on a large lot, owned by a man seldom seen. He hated children, and they must have been in school the day he bought the house, not suspecting that when the last school bell rang the neighboring yards would overflow with unpredictable and sometimes destructive children. Counting the six or seven homes that were the closest to him I can name fifteen children.

He hunkered down in his big house and even nailed a no-trespassing sign on the tree where you entered his long curving driveway. We

ignored the sign and used the drive frequently. The drive had a nice dip and curves

in it when we rode our bikes down it, and then we’d coast all the way around to the

back to where his garage sat. It was also good for sledding.

He wouldn’t answer the doorbell when kids like me were collecting for the March of Dimes, or selling scout

tickets and Christmas holly, etc. He must have had one of those little eye holes

in the door to screen out small salesmen. His first option was to call the

police when we trespassed.

Sherry said she and some neighbor friends

filled a paper sack with some cow dung, placed it on his front porch, set a

match to the paper sack, rang the doorbell, and then ran and hid behind the bushes.

Squinting with one eye through his little peephole and seeing no one he might

have marked it up as just another harmless prank to irritate him until he saw

a whisper of black smoke rise from his porch.

Alarmed, he unlocked the door, opened it, and saw the burning sack. He

vigorously stomped out the fire wishing no doubt he had bought a house in a

quieter area with no school nearby. We

were in an inner-city neighborhood with a few chickens but no cows, which brings

into question the origin of the shit in the sack. We had a surplus of mixed-breed dogs. I’m sure that whatever animal

contributed to the poop, it was on the crank's shoes or slippers as he tracked back

through the house to the phone, where he immediately called the police.

Sherry, not one to flee the

scene of a crime, says that when the policeman left the crime scene and passed them hiding behind the

shrubbery, he whispered “Good job kids!

Sherry, not one to flee the

scene of a crime, says that when the policeman left the crime scene and passed them hiding behind the

shrubbery, he whispered “Good job kids! Sherry was Dale's go-to when they were young, and it was again Sherry that Dale went to in High School when he needed a note signed that came from the Northeast High School Principal. A tidal wave of correspondence arrived in our mailbox concerning Dale's absenteeism. Dale and his buddy Wally would skip school and spend the day in the pool hall next to the barbershop in Fairmount.

Sherry penned Mother's signature so accurately it would have taken a handwriting expert to detect the difference and in addition improvised novel works of fictional excuses for Dale's absences.

Sherry's big reward for the forgeries came after Mom found the cache of letters during a routine flipping of Dale's mattress. Mom took Dale to the Naval Recruiting Station in Kansas City and he was soon boarding a train at the Union Station headed to boot camp in San Diego California. Sherry says Dale left his car for her to drive to school her senior year. It wasn't the 32 Ford Coupe with the rumble seat or the big Chrysler he bought for less than a hundred dollars. It must have been the 1939 straight-eight Oldsmobile. I've lost track of which one it was, but it had a stick shift.

Sherry couldn’t wait to earn a

little money of her own. She says she was never overly fond of schoolwork. At a young age, she started babysitting for our

next-door neighbor's boys, Kenny and Johnny Musgrave, and then any other

neighbor kid that Judy wasn’t already babysitting. She snagged a job at the

Five and Dime in Fairmount. and worked there for two weeks helping with inventory

and neatly stocking the shelves. She earned praise from the owner until he found she

was only 14 and too young to be legally working. She found a job soon after working at the

Byam Theatre, possibly with a recommendation from Dale, who had been

a dependable worker at the Byam Pharmacy cleaning up and delivering

prescriptions on his bicycle.

In her junior year while still at Northeast High School Sherry found a part-time job at a plastics factory in the Italian District, near the industrial west bottoms. She would board a city bus to school that entailed several transfers, and then after school, she would catch a bus to the job. Following work she would board another bus for the long ride home. I imagine after a four-hour shift it was probably dark by the time she made the last bus transfer to Mount Washington. Then the last bus would leave her at Fairmount and then she would walk down Huttig in the dark to our home.

Sherry says Mom was a terrible driver. She would get mad when Sherry told her she was driving too close to the edge of the road. I remember Mom telling me that her Dad was a terrible driver, and would drive too close to the edge. Mom said if you criticized him, or tried to warn him of an approaching train, or some obstacle in the road, he would just slam on his brakes with no concern about who was behind him.

Sherry was popular and pretty and dated early. She was active in Zion's League at Gudgell Park and she had plans to marry Vernon Sperry. He had a mile-wide jealous streak and was upset when Sherry made plans to attend Graceland College in Lamoni, Iowa. He showed up at the house with his mother and they angrily took back the ring he had given her. They also took the hope chest and all of its contents. Vernon's comment that Sherry was just attending Graceland to meet boys turned out to have some merit. That's where she met her future husband David Ackley.

There are a number of

interesting little bits and pieces of information I have written down about

Sherry that I can’t thread together in any coherent manner.

Sherry’s favorite meal at

Fairmount Elementary was cornbread and beans with vinegar.

Sherry remembers a female high

school science teacher who had the mannerisms of a man. She wore an ill-fitting

wig, and while lecturing she would sit on the edge of her desk constantly

adjusting her girdle and pulling up her bra. When the students learned she was

allergic to roses they would bring them, and she would place them on her desk

instead of throwing them out. Then they

would have a substitute teacher for several days until she recovered.

A few years ago a sudden change in temperature caused Frostflowers to erupt in the old abandoned homestead at the bottom of the hill. It looked like iced cotton candy spinning out from the fissures at the base of Ironweed and other weedy plants. I stood with my sisters Judy and Ruth in the middle of this weed garden of Frostflowers stunned by the beauty of it. It was momentary art that none of us had witnessed in all our combined years. The sun soon melted them but it made me reflect on the fleeting nature of our existence. I realize we are all Frostflowers, impermanent and fragile.

No comments:

Post a Comment