Unless you were abandoned

and raised by wolves you can probably name the people who influenced you the

most in your childhood. Those names and faces rise from whatever part of your

brain good memories are kept. There are a lot of good memories from my

childhood that include my sister Judy Jo.

|

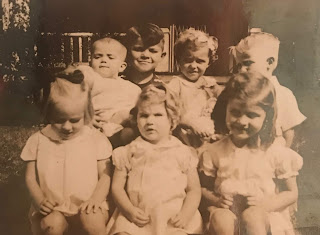

| Me and Judy |

After the trauma of the airplane crash that killed our

father Judy often took on the role of surrogate mother and mentor to Ruth and

me. Before we get to stories of blue paper mache giraffes and man eating

neighborhood cats we need to back up, and review a few of the incidents in Judy

Jo’s early youth that lead to her moniker “ The Wild Child.”

Early in the morning September

24th, 1936, mom woke with no labor pains, but with the

realization that Judy had suddenly turned into position to be born. Our father quickly drove mom the four miles

to the hospital. Skipping over the usual

labor pains that precede most ordinary births the nurses realized this unborn

child was in a hurry. The nurses weren’t able to finish the pre-op

procedures. Mom wrote this:

“They put me on a cart and

ran pushing the cart and me as fast as they could to the delivery room – I can

still see my stomach swaying as we went around corners. Judy never did care to wait

around and started to come out. Dr.

Grabske had one arm in his white jacket and told Sister Hattie, Hold her back!”

Skipping ahead past the normal wrinkled

and frankly unattractive newborn that prompts worried parents into asking “are

you sure that’s our baby?” mom writes this:

“A beautiful baby girl, over ten pounds, a perfectly shaped head

and body, dimples in her rosy feet and hands, very fair, no redness or wrinkles

like most newborns.”

Judy was innocent

enough in her first encounter with gravitational force when three year old

Brother Dale wanted to take a good look at his new baby sister, and while

peeking over the side of the bassinet, he unintentionally pulled it from the

stand it was precariously perched on. Mom said Judy s nose was bruised and

turned black.

The next incident was a little prelude to the challenges mom

was to face while corralling Judy Jo.

In

1937 our parents were still shoveling coal into a huge old style furnace in the

middle of our basement. Octapal gray metal arms branched up from it and fed

heat into the floor vents of the rooms upstairs.

The dining room floor vent was the hottest,

being directly above the furnace, and a favorite place to thaw out in the

winter after playing outside. When Judy was eleven months old mom had to tend the

furnace, so she wrapped Judy up as tightly as she could in her blanket and told

her to stay quiet. Judy was an early walker and had already been running around

helter skelter for several months.

She

was probably out of the blanket before mom was halfway down the stairs.

When mom came back upstairs Judy was standing on top of the

red hot grate. Her feet were burned and blistered so bad that it left deep

scars in the bottom of her feet. When

mom would doctor her, Judy would look into mom’s sad eyes and try to make her

feel better, a promising glimpse into the future caring person she would become.

Not yet though, she had to live up to her “Wild Child” fame.

There were many calamitous consequences from her untamed nature that didn’t seem to curb her unruliness one whit. As an infant, in a Houdini maneuver, she

extricated herself from the tray that locks a toddler into a high chair, and

standing on the tray itself, launched her small body off it to short-lived freedom,

resulting in a broken collar bone.

Always a quick step ahead of normal Judy Jo arrived at the

“terrible two’s” a half year early.

Our

kitchen was actually not much more than a narrow hallway. The stove and

refrigerator were on one side, and the cabinets and sink on the other.

You could turn from the sink to the stove

without taking a step. One day my mother, the dog lover, allowed our neighbor’s

Saint Bernard into the house.

He settled

down and went to sleep between the sink and the stove and blocked foot traffic

completely.

Judy could block

traffic just as successfully. She loved

opening the cabinet doors, pulling out the pans, and crawling in herself. Mom laughed the first few times, but one day

she tied the cabinet doors together with string. “Wow, was Judy mad,” she writes in her journal.

Judy threw a “terrible two’s tantrum,” a 9 or 10 on the fits

of temper scale. Mom tried ignoring her at first, without even a hint of success.

Mom then escalated to “phase two” of

behavior modification. She poured water on Judy’s head. Still unsuccessful in

quelling the screaming and kicking with “water boarding,” she put Judy in a

closet so the neighbors wouldn’t think she was beating her. We don’t know the length of the internment in

the closet, but as soon as she saw daylight Judy went right back to the

kitchen, screaming and kicking in front of the cabinet doors mom had tied shut

with string.

At wits end, mom turned to the Lord and prayed, and received

an unusual answer you won’t find in the scriptures. An inspired idea came to her, and she

cautiously looked out the back, and then looked out the front of the house. She went back to the kitchen and got down on

her back on the floor beside the Judy who was still in full “fit” mode. She

started screaming and kicking her feet to match Judy’s tantrum.. Pretty soon Judy stopped, sat up and looked

at mom with big round eyes. Alarmed at her mother’s bizarre behavior, she then

back pedaled out of the kitchen as fast as she could into the safety of the

front room. Mom writes: “That

was the end of tantrums for that little girl.”

Although mom had checked the front door, she failed to see

the mailman approaching from the neighbor’s yard. In the summer we left the doors open for air

flow, leaving only the screen doors to keep out the flying insects. The mailbox

was on the front porch, and the mailman had an unobstructed view into the house

through the screen. We don’t know what

he thought when he saw a small wide- eyed toddler watching her own mother kicking

and screaming on the kitchen floor. Mailmen

probably witness a lot of abnormal behavior on their daily treks through a

neighborhood. Perhaps he thought mom had joined the Holy Roller Hickman’s

across the street, or more likely he had witnessed some of the daily activities

of the “wild child” and thought “that poor mother!”

I may have some of these incidents chronologically out of

order, but it’s all too apparent by now that Judy Jo had things to do

and places to go.

She didn’t appreciate

being constricted or subjected to the normal norms of behavior, which brings us

to the celebrated “streaking” event. At eighteen months old Judy was a runner

with good hand eye coordination.

The

screen door latches had been raised to keep her in the house.

Mom gave Judy a bath, and after toweling her off the unadorned speedster took off, through the dining room, through the kitchen,

grabbed the broom on her way, through the back hallway, then used the broom to

unlatch the screen door without breaking stride.

Mom was in hot pursuit, but no match for the runner.

Wearing not a stitch, and

still running, she went around the house, straight out into the busy

street.

The street we lived on was well

paved and used by the city transit system. It wouldn’t be a really memorable

story without a bus, and of course

there was one barreling down on the “streaker”

just as she entered the street. There were no doubt passengers thrown from

their seats as the bus driver swerved and jumped the curb in front of Mr.

Powers home across the street. Luckily no one was injured and little Judy Jo was intact and pumped

up for her next adventure.

It didn’t take long for Judy to find her way back to the

kitchen. The cabinet doors to the pots

and pans were secured with string, but the doors beneath the kitchen sink were

not. The only things there were water

pipes and a large can of lard. This early tactile experience may have been the

gateway to her later interest in art and paper mache.

Mom was on the living room couch,

exhausted from keeping up with Judy all day. She was having a rough pregnancy

with Sherry. To top it off the unpleasant smell of wieners and sauerkraut cooking

in the kitchen was making her green around the gills. Dad was in the chair

directly across from mom, totally oblivious to the experimental art work going on

in the kitchen. With pride from the tufts of kewpie doll curls she had created

on her head with the lard Judy crossed through the dining room to

the couch and proudly tapped mom softly on the knee. When mom saw the cotton ball curls of Crisco

on Judy’s head fluffed out like good meringue on a lemon pie, she moaned (another version says she screamed)

“Go see what Judy’s done this time!”

Dad put down his newspaper and reported back that the lard can was empty

and its contents were smeared on top of everything Judy could reach, including

the floor. Dad manned up, since mom was

down for the count, and cleaned up the kitchen, possibly with the newspaper,

since paper towels weren’t a thing yet.

There is one more curious little incident that I hesitated

to include but it actually puts an exclamation point on whether Judy Jo truly

deserves the handle of the “Wild Child.”

While still in the “running around nude stage” Judy would pull all of

her clothes out of her dresser drawer and pee on them. Seems like out of the ordinary behavior

unless you actually were a feral child raised by wolves. Mom brings it up because she had to rewash

all the clothes in the dreaded Maytag wringer washer, the only appliance I ever

heard my mother swear at. Judy is

perplexed on why she did this but thinks it’s because she was worn out from the

day’s frenetic activities, and a reluctant inability to make a decision on what

to w ear. Standing there on the pile of unwanted clothes, she just couldn’t

make it to the bathroom in time. Maybe,

but I don’t buy that explanation fully.

It’s possible she was

marking her territory. like a feral animal might, but I don’t buy that either. Mmmm?

Maybe a little.

|

| Judy and Dale |

I think peeing on the

clothes was an act of protest against the unnatural convention of having to

wear clothes. Grudgingly over time, Judy buckled to society’s

norms and was decently covered by the time she entered kindergarten.

Like Judy, my most vivid memory of elementary school was a

trip to the woods in kindergarten.

I

wonder how many of Mrs. Flowers students were nudged towards careers in science and education by her influence. She gathered the

entire class near the jungle gym and paired each of us with a partner. We had

no idea where we were going as she lead us down us down the short set of steps

to Cedar, the street that flanked the school on the west side.

We headed north up the street towards the

woods that lead to the

Missouri River. Mrs. Flowers kept

a close watch over the rambunctious bunch of five year olds, repeatedly warning

us not to let go of our partner’s hand.

I had been hoping for a girl partner but got Gene Pittman, who hated the

pairing as much as I did.

We were still

clueless as she led us off the road into the woods where she proceeded to tap some

kind of spigot into the trunk of a tree and hung a silver bucket on it.

I can see why this is one of the most vivid

memories of the “Wild Child,” though by now she was only half wild.

The next trip to the woods was to collect the sap and take

it back to the classroom.

I still had no

idea of the significance of the activity.

The kindergarten class was a large room on the basement floor near the

cafeteria, but Mrs. Flowers had set up her own little children’s kitchen in her

classroom. We all milled around the stove and the slow- slow-slow process of

converting the sap to syrup.

Then the

syrup was magically converted to maple candy, and while other teacher’s names

have been forgotten, I will always remember hers.

Finally all the coming and going to the woods

came together and made some sense! The hike to the woods was fun and memorable

in itself; taking sap from a tree was at first a puzzling procedure to me, but

then there was finally the magical conversion of tree sap to maple fudge candy.

I circled the little classroom kitchen and got in line for fudge a second time,

but there was no fooling Mrs. Flowers.

Judy says in her class they made maple syrup from the tree

sap and put it on pancakes.

I promised

not to dwell on my sister’s adult lives, but I can’t help but wonder how much

Mrs. Flowers affected a five year old half feral child who later became a

consummate science and nature loving teacher, who in retirement tapped trees at

the

Burr Oaks

Nature Center

and taught wild edibles classes.

|

| Judy on the right age 8-10 |

We catch another glimpse of eight year old Judy in 1944,

through letters written by mother to our father, who was training pilots in Kansas

for the war.

“Judy

had a little skinned place on her knee this morning and tried to pretend she

couldn’t walk, but I finally got the poor little invalid off to school, much

against her will!”

“Last

two mornings Judy has been so mad at me because I made her put on galoshes that

she said she was going to walk to school real slow and be late. Yesterday she started out walking as slow as

she possibly could, but when she heard the school bell you should have seen her

coat-tails fly!”

I can sympathize with Judy about those wretched oversized

rubber galoshes that sat at top of the basement stairs as a perennial safety

hazard. They were still there when I was

in third grade, when I had a part in the school’s Christmas play. Bundled in a large coat, gloves, and stocking

cap I looked like the kid in the “Christmas Story” that couldn’t get through a

door. I was to enter offstage, run

across the stage with a sled that had wheels, plant it midway, and glide

offstage on the other side. I had done

it three times in practice without incident, without the rubber galoshes. Mom insisted at the last moment that the

galoshes looked better and more in the Christmas mode than my dirty tennis

shoes.

The evening of the well attended play, in floppy galoshes three

sizes too big, I came running on stage, stumbled, awkwardly planted myself

facedown on the sled, and slid off the front of it, mid-stage. So Judy and I share the same loathing of

those rubber galoshes.

The anger Judy had towards those detested galoshes may have

lead to the next event. She was forced to wear those over-sized men’s galoshes

to school, which had to be an embarrassment to a girl that had just recently

been domesticated. Mom’s letter about Judy being so mad at her for making her

wear those galoshes was written in 1944 so Judy would have been eight years

old. There must have been rain that day,

therefore the galoshes.

I have no direct

proof that the galoshes lead to this little confessional that I found in one of

my sister Judy’s later stories. It does seem in character for a partially

domesticated little girl.” I can see this happening after school with the

ground still partially wet and Judy still furious over the boots.

“I’m

always in trouble for something. Mr. Francis must have seen me when I was

throwing dirtballs at the cars going by and this guy had his back window down

and my dirt ball ended up in his back seat. He stopped and I ran and hid behind our house.

He went to our front door and told my

mom and she made me clean out his car with a whiskbroom and dustpan. I should have run behind someone else’s

house.”

In another letter in 44 mom writes:

“Judy

has broken one of the windows up at Linhare’s house. I thought that little

girls didn’t do things like that!”

I lose track of Judy for several years since I was busy

re-purposing the chicken house into a fort, and Judy and Sherry had begun

“sashaying down the street” as mom puts it.

Most of the time they were “sashaying” over to the Terhune house that sat

across the street from the ogre’s circle driveway we were not allowed to

use. Mr. and Mrs. Terhune were shorter

than average Catholics, and they had four diminutive daughters. At age six or seven my sister Sherry and one

of the Terhune girls entered a talent show.

Phyliss Terhune and Judy ran away via public transportation

at one point, and Dale was sent to retrieve them. I think it was about this

time that Judy and a bunch of girls tried their hand at smoking over at Donna

Laugherty’s house.

In the fifties there

were a lot of Lucky Strike ads that started with “More Doctors Smoke Lucky

Strikes,” and then there was an ad with a teen age girl dressed for the prom

with a dance card in her hand and a Lucky Strike cigarette held elegantly with

two fingers outside the dance card. It was the cool thing for teenagers to

smoke in the fifties.

Judy, Jeanette

Gerber, Donna, and two other (Terhune girls?) teenagers smoked an entire

carton of cigarettes that evening. A carton contains ten packs.

With 20 cigarettes in a pack that totals 200

cigarettes.

They smoked the entire

carton.

Judy says she got so deathly ill

she thought she was going to die.

To

this day she can’t stand the smell of tobacco smoke.

|

| Ruth, Me and Terhune girl on the right |

The prettiest Terhune

girl ended up on the Jack Lalanne show helping Jack sell food blenders. I

mention the Terhune girls because there seemed to be a lot of girl stuff going on

over there at their house which included my older sisters, but that was a girl’s

mystifying and confounding world. I was only interested in what western was

showing Saturday at the Byam Theatre. I

loved the Lone Ranger and Tonto movies that came with a Looney Tune Cartoon. I didn’t care much for the world news. Shown

in black and white there was news about the end of the Korean War and bomb

tests in the Marshall Islands,

which seemed a world apart from important issues happening on South

Huttig Street.

From the ages of 12 to 15, when the question came up in our

neighborhood and beyond on who would you recommend for a baby sitter, Judy’s

name was at the top of the list. Maybe mother had sealed her lips about Judy’s

early behavior, or maybe it was because there was no antic or behavior a kid

could come up with that Judy couldn’t anticipate or handle, having been there

and done that.

Judy developed a network

of babysitting jobs that swelled to 22 families, and untold numbers of

children.

She earned twenty five cents

an hour.

I remember one of her jobs was

in a house off of

Winner Road

past the High School that looked like a castle covered in aluminum foil.

|

| Judy around age 15 |

For some inexplicable reason, at least to me, I suddenly and

unexpectedly was a beneficiary from many of those hard earned quarters Judy was

squirreling away from her babysitting.

We had a small cherry tree on the north side of our house. I came around

from the back of the house through the little gate that lead to the side yard

and Judy was standing by that cherry tree holding a brand new English styled

maroon racing bicycle.

It looked like

the imported ones in the

Raleigh

ads in “The Boy’s Life” magazine, with small racing tires and hand brakes.

It looked nothing like the heavy and fat

tired Schwinn I had been riding.

It

wasn’t my birthday, not even close to Christmas, so I was perplexed.

Judy had that impish smile at seeing my

complete surprise. I can only presume she was paying forward, before it became

a thing.

If this wasn’t enough to cement

my undying affection for my sister Judy, the best was yet to come.

In 1953 the cold war was heating up, Dwight Eisenhower

and his side-kick Nixon were inaugurated President and Vice-President, and Jonas Salk was trying out the polio

vaccine on his own family members. The things that concerned a ten year old

like me were the rising price of the Saturday matinee, fear of contracting

polio, and the premier event that happened in our inner-city neighborhood every

year in October. The Fairmount Pet Parade.

In

1953 and 1954 I would get my taste of fame and revel in seeing my name in print

in the local rags. Very little of it, I realize now that I’m older and wiser,

was due to my own efforts. The two Pet

Parade triumphs were orchestrated almost entirely by my sister Judy.

In 53 I was ten years old, and one of the 350

inner-city kids who would compete for trophies and ribbons in the Pet

Parade. There were ribbons given out in

different categories: Smallest dog, largest dog, dog with the longest tail,

shortest tail, longest ears, on and on with similar categories for cats.

There were other categories for kids who

brought turtles, snakes, and ferrets. There were ribbons for the best decorated

bikes and the best combination Halloween pet and owner costumes. My younger

sister Ruthie won second place in this category dressed as a Genie carrying a

small cage. I think Judy made the costume, and the cage might have held Judy’s

parakeet.

Then there was a foot high trophy for the

best overall float. The following Tuesday

a long article in the “Inner-City Sentinel leads with:

Daniel Sherman Sweepstakes Winner with

Caged Tiger. Danny’s

float consisted of a cage mounted on a wagon which contained a ferocious

man-eating tiger. Atop the cage was the

limp effigy of a man whose unfortunate association with the beast resulted in

his decapitation. The roaring carnivore

within the cage, however, was naught but a timid kitten.”

|

| Timmy Bly on right who as an adult joined the "Hell's Angels." |

Let’s break this down. Judy did most of the work converting the

large cardboard refrigerator box to a barred cage, made the life sized stuffed

effigy that laid atop it, made my circus ringmaster’s outfit, including a top

hat, bow tie, and a coat with tails. She

somehow also found a kitten in our dog loving neighborhood. The float was not sitting on a wagon as the

reporter reported, but on a cart I had made from scrap lumber earlier that

summer. So the cart at least was mine,

and I got to parade in front of the float for an hour as the parade went right

down the length of the Fairmount Business District lined with 500 or more

spectators. Timmy, Kenny, and David, members of the “Chicken House Gang” pulled

the float and I walked in front of it cracking a rope whip that Judy made. Life

was good, especially when I was handed a foot tall trophy cup inscribed with

“Best Overall Float.”

Did I

announce at the ceremony “I’d like to give a little shout out to my sister Judy

who did most of the work?” No, I was ten

years old and reveling in the publicity, and a new elevated status in the

pecking order of the “Chicken House Gang.” The icing on the cake was witnessing

the takedown of our “Gang’s” arch enemy, John Cernech, the rich doctor’s kid

who lived up the street in the white house with the white fence that kept his

purebred pets, swing set, and toys away

from the mongrel mixed breed dogs, and riff raff like ourselves. John Cernech, even with his brand new store

decorated bike got only a third place ribbon, and his younger brother Bill

didn’t even place. My sister was improving my life in every

category.

The “Pet Parade” in 1954 turned out almost as

good. Judy, with her off the wall

imagination, was again the power behind the scenes. She came up with an idea

that placed Ruthie and I at the exalted pinnacle of Pet Parade dominance. The crowd was down a little because it was

chilly, but the participants showed up in the hundreds because every kid got free

dimes and five pounds of dog food, plus a free pass to the Saturday matinee at

the Byam Theatre, showing two Zane Gray movies

and four cartoons.Eight year old Luann Leach literally stole

the first place trophy with a tricycle that had been extended on both ends with

an elaborate framework to resemble a battleship. It was covered with crepe paper in patriotic

colors. First of all, her float had already won prizes in a Fourth of July

Parade months before somewhere else, and should have been disqualified. This was

a Halloween themed Fairmount Pet Parade, and it was obvious with the intricate

framework that no third grader made the float, but who was I to lodge a

complaint?

If I

had been interviewed by a reporter or grilled by Hal Roberts, the master of

ceremonies, about how I had come up with such a unique idea as a blue giraffe

the jig would have been up. Judy had

spent hours, and then more hours, wetting and applying home made glue to strips

of paper to assemble a 7 foot tall paper mache giraffe. Then Judy painted it

blue, added white spots, big eyes with extra long black eyelashes, and with two

cardboard yarn cones added two of those bulbous giraffe knobs on top of its

head.

This was not an entire giraffe, just a 7 foot

tall neck and head that I balanced on top of my head with the aid of a

broomstick handle. For the body Judy coordinated

a blue and white spotted fabric over Ruthie and me so only our legs were

exposed. She put two very small eye

holes in the front of the fabric so I could guide the giraffe down the parade

route. Ruthie really got the bad end of the deal because she was the rear end

of the giraffe and had to hold her head down so she didn’t poke her head up and

make us look like some mix of a blue giraffe and a one humped spotted camel. In addition to the difficult task of trying

to follow my lead and match my step rhythm, she had to reach behind herself

with one hand to constantly wag a rope tail.

I had no peripheral vision at all. We were constantly bumping into things and

out of step, with Ruthie headed one way and me another. The police had shut off

one complete lane of U.S. 24 Highway, and although I couldn’t see, I presume we

passed by the same buildings we had the year before, a little non-descript

restaurant, a service station with two open bays, a Firestone Store, the feed store where we

bought chickens, Charlie’s Market, actually owned by two brothers, neither of

them named Charlie, a hardware store where I bought nails for kool-aid stands

and carts, Roy Mennis’s Inner City Appliance, where mom bought the Maytag with

the wringer washer she swore at, then the Standard State Bank where we never

had a savings account, then a couple of stores I never had interest in because

they had to do with women’s hair and clothes. Because there were so many

entries the parade organizer lined all the entrants four across. I imagine the trikes and bikes in our row were

constantly trying to avoid the blue giraffe that was weaving and meandering

blindly down the parade route. The crowd lining the streets probably thought it

was part of our act.

At the awards ceremony, the giraffe somehow

made it up onto a flatbed truck bed where the trophies and ribbons were being

awarded, and Judy said both of Ruthie’s hands came out from each side of the

fabric that was covering us to receive the trophy. Adding to our ascendancy in

the neighborhood pecking order Ruthie and I won first place ribbons in the “Most

Unique Pet” division. John Cernech, our arch

enemy rich neighbor, with his high dollar dog and new clothes, merely won a

ribbon in the “Best Dressed Owner and Pet” category. Davy Bly, one of the poorest kids on our

block, and long time member of our “Chicken House Gang,” won a first place

ribbon for the dog with the longest

nose.

|

Judy 1954 - Senior Photo |

A few years ago I visited my sister Judy at

her booth at the Rock and Mineral Show in Kansas City, Missouri. For many years she has set up an educational

booth to share her rocks and mineral collection with the public, especially the

youth. I was prompted to write this

after the visit. Like our mother, she

recognizes God’s presence in all of nature.

Spring Offerings

This is your gathering of stones

Wrapped carefully in paper and cotton cloth

These are not familiar field stones to form walls

Or perimeter stones to mark boundaries between neighbors

There is not one grindstone - useful as they are

These are astonishing stones gathered

From fractured fields and broken valleys

Rose quartz, hornblende, agate, schist and shale

Each year in mid-march you carefully un-wrap these stones

To be shared as a communal gift –an offering if you will

To those who wish to stop at your spring garden of stone

Where you’ve carefully labeled and separated

Meteoric stones fallen from broken stars

From those spewed through volcanic fissures

From tins and cartons come your surprising stones

Feldspar, blue schist, gneiss, green veins of malachite

The purple altars built crystal by crystal into amethyst

There are oddities formed from lightning strikes

And magnetic stones and curious floating stones

Stopping students and scouts in mid-stride

I unfairly asked you to pick your favorite

And you turned in a slow constrained circle

In the middle of your museum considering

But it was not long before you led me to a closed tower

And carefully reached in to gather in your hand

A mystifying illusion called Labradorlite

When you held it to the light it was translucent

Shimmering an aurora of indigo and streaks of gold

Depending on how you positioned it

This stone is more than a product of heat and pressure

More than a mere complex crystalline structure

Shaped slowly by the physics of ions and diffusion

It is a mystery-and I know its ghostly transparence

Fires your imagination- and its flashes of color

Bring you joy and a sense of oneness with the earth

Fold that one carefully in a soft cloth when you bundle it

As if it’s a small bird with a beating heart

“